Trailblazer

trail·blaz·er /ˈtrālˌblāzər/

one who leads the way in any new field or endeavor; pioneer

Fridays With Fred: Velma Bell and Beloit

The story of the first black student to become a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Velma Bell

By Fred Burwell ‘86

Beloit.edu January 13, 2011

“For the first time in the history of the Beloit chapter of Phi Beta Kappa – and that extends back some 18 years – a colored student has been elected to membership. She is Miss Velma Bell of Beloit, graduate of Beloit high school, and a student of remarkable attainments. Miss Bell has received no grade lower than a ‘B’ during her college course and has amassed so many grade points that she will have almost three times as many as she needs by the time she graduates in June. She has earned almost all of her way through school in addition.” – The Beloit Alumnus, November 1929

Velma Fern Bell was born in Pontotoc, Mississippi and came to Beloit with her family in 1914. It was a period when African Americans were migrating from the South to work in Northern factories, and Fairbanks-Morse and Company of Beloit hired many laborers from Pontotoc, including Bell’s father, Walter. The family eventually settled on Elm Street on the west side, and Bell attended various Beloit schools. “I went on to high school after 9th grade,” she said in a 1996 interview, “and one of the teachers there…said to me, ‘I hope you’re going on to college.’ I remember that. And of course I had assumed that I would. It never occurred to me that I wouldn’t, but no teacher had ever said that to me.”

She graduated from Beloit High School in 1926, one of the top five students of her class and a member of the National Honor Society. Due to the economic climate of the times she was unable to go away to college as she hoped and so she attended Beloit, walking across the bridge to campus each day. She immersed herself in her studies and found work taking roll for the thrice weekly chapel and vespers services.

“Opportunities to develop leadership skills open to most college students were limited for me because I was a ‘townie’ and lived on what was then the ‘far west side’,” she wrote in 1985. “After classes, library study and required college activities such as chapel and vespers, I went home and did not return to the campus for recreation, student government, or social participation in small student groups (nor was I encouraged to do so).”

Tuition expenses grew beyond her means and she found it difficult to find meaningful, well-paying work, according to a January 1929 letter to the college. “During the summer the only work open to girls of my race, especially, is housework which, as you know, is not very remunerative. Although I have received all of my education in Beloit – from first grade to college – I seem to be thought unworthy to hold the positions which my friends hold…” The college was determined to do what it could and arranged a small scholarship, followed by a successful application to the Julius Rosenwald Fund on her behalf, which helped fund her junior and senior years. A letter of support by Professor Lloyd Ballard described Bell as “a student of marked ability and of genuine earnestness.”

By the fall semester of her senior year, Bell’s reputation as one of Beloit’s finest students was firmly established. That October, Beloit College Dean William Alderman wrote to Bell, “It gives me great satisfaction to be able to extend to you my congratulations because of your election to Phi Beta Kappa. This coveted honor was in your case a much merited one. In these days of unsolved problems those who have minds to discern and wills to execute will inherit a great responsibility. I shall follow you with expectation as you go on to further preparation and as you finally take your place in and make a place for yourself in the work of the world.”

As part of her sociology major, Bell wrote a brilliant thesis entitled Race Prejudice, which gained her departmental honors, one of only six students honored college-wide that year. “The cry of the Negro is one with that of all the darker peoples,” she wrote. “They want freedom from economic exploitation; they want to participate in whatever economic system touches them on the basis of their merit as individuals; they want freedom from political dominations; they want their real interest represented in whatever government rules; they want an education, not one which will fit them for a certain subordinate status, but an education that will fit them to make a living in the world as it is; they want the stigma of inferiority lifted from them so that they may be able to walk down the streets of the world and into the common gathering places of mankind free from contempt. They ought to have unfettered opportunity for the realization of these hopes. Should such attitudes and desires be treated with unreasoning, intolerant prejudice?”

On June 16, 1930, after only three years of study, Bell graduated from Beloit College magna cum laude.

A 1985 letter commemorating the anniversary of 90 years of women at Beloit College found her reflecting on her student years: “We came along after the first women had proved their intellectual competence (which many had doubted when women were first admitted) and their abilities to enhance the quality of college life. But equally important, we were in on the ground floor of new choices and new opportunities brought on by cultural and social changes. We were exposed to a broad base of knowledge; we were acquainted with the elusive nature of truth and the need to continually search for it; we were taught (hopefully) to think, to expect and accept change; it gave some of us the successful experience of breaking down barriers; we had opportunities to develop confidence in ourselves through academic achievement. This kind of environment during my four years at Beloit was for me the ‘open sesame’ for whatever I have accomplished since graduation.”

And she achieved much. Following graduation, Velma Bell taught at Bennett College for Women in Greensboro, North Carolina. She received a Master’s Degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1933, having written a thesis entitled, The Negro in Beloit and Madison Wisconsin. In 1934 she married fellow educator Harry Hamilton. She had a distinguished career in Madison, Wisconsin, where she taught at the Madison Vocational School (now Madison Area Technical College), sat on the boards for the governor’s Commission on Human Rights and the Wisconsin Committee on Children and Youth, was a charter member and president of the Madison branch of the NAACP, was named Citizen of the Year in 1961 and Wisconsin Mother of the Year in 1974.

In 1968 she became Beloit College’s first African-American trustee, serving until 1971. She received a Distinguished Service Citation in 1965 and an Honorary Degree in 1991. Two of her three children, Harry Hamilton Jr. (long-time Beloit College trustee) and Patricia Gyi, are graduates of Beloit College.

Velma Bell Hamilton passed away on July 9, 2009 in Atlanta, Georgia.

Frank Clarke

Beloit Daily News, Monday May, 29, 1967

By Ed Plaisted-Daily News Sports Editor

Today is “Frank Clarke Day” in Beloit. How does he feel about it?

“I feel very good having a day in my hometown,” he said humbly. “It’s a fine tribute. There will never be any finer. Even in my wildest dreams as a kid I could never have imagined such an honor. I think it’s a real fine honor. And it’s one I’ll always remember and cherish.”

Frank’s entire family, his parents Edwin and Ada along with his brothers Ed, David, George and his sister Roberta gathered at the Beloit Memorial High School to hear their son and brother speak at the All-Sports Banquet. Frank was back home where it all began for him many years ago. Beloit, the place where he made his mark in football, track and even basketball as far back as a student at Lincoln Jr. High School.

Franklin “Frank” Delano Clarke, the son of Edwin and Ada Clarke was born on February 7, 1934 in Beloit, Wisconsin. Growing up, Frank attended schools within the Beloit Public School system. A student at Burdge Elementary, Lincoln Jr High and onto Beloit High School. Always surrounded by family and friends growing up, a very energetic and active young Frank stood out with his athletic ability.

Frank’s high school years were not only about athletics, a very popular student, he was involved in a number of school clubs and held class office positions.

Senior class officers included Frank Clarke as Vice-President, he was also a member of the student council.

Seated on the second row, sixth person from the left, Frank was president of the B-Club. The B-Club was composed of young men that were awarded letters in athletics.

Frank, back row third from the left, was a member of the Badger Hi-Y.

Frank Clarke excelled in football, track and basketball throughout his high school years. As co-captain of the varsity football team, Clarke helped to lead the team to six victories and two defeats, finishing in a tie with Racine Horlick for second place in the conference.

The varsity basketball team elected Clarke, a forward, as one of their co-captains his senior year, also earning honors at the end of the season.

Frank crosses the finish line well ahead of his competitors at a track meet held at Strong Stadium. Pictured on the right is Frank with his 880-yard relay team members (left to right) Frank Clarke, Tarzan Honor, Laverne Bradford and George Foster.

Frank Clarke finished his senior high school year as a stellar athlete, a threat on the football field and a speedy trackster on the cinder lanes presented him with All-State honors, a WIAA State Boys Track & Field Team Championship and track records that weren’t broken for years.

Frank D. Clarke graduated from Beloit High School in 1952, his classmates voted him most athletic out of the entire class.

Frank Clarke had a brief stint at the University of Wisconsin before taking his football talent to Trinidad Junior College located in Trinidad, Colorado, where an assistant coach on the football staff had a connection to Beloit. Coach John Thiel, a former athlete at Beloit High School, invited Frank and his teammate Tarzan Honor to join the Trinidad football team and they both accepted. Trinidad Junior College soon became a pipeline for several other African American athletes from Beloit. Dick Gupton, Charles “Choo-Choo” Gladney and Dick Franklin from South Beloit, Illinois soon joined the football squad, Trinidad’s football team improved drastically with the addition of Frank and the other Beloit athletes. One highlight came against La Junta Junior College when the final score was 73-0, with seven of the touchdowns being scored by the Beloiters. Honor scored two, Gladney scored three and Gupton and Clarke each scored once. Frank and his teammate Gladney earned All-Empire State conference first team honors.

After playing two years at Trinidad Junior College, Frank transferred to the University of Colorado in 1954, where he joined John Wooten as the only two African American players on the team. His decision to play football at CU made him one of the first of many. Frank became the first African-American to play varsity football, the first to earn a letter at CU and first African American to play football in the Big 7 Conference. Despite only a handful of African American students at CU, he was well received by his fellow students and teammates. His popularity on campus was capped off when the students elected Frank king of the annual CU Days Festival. This honor is equivalent to being crowned homecoming king. Jet magazine featured Clarke in their June 28, 1956 issue.

Colorado’s offense was built around a single wing system, leaving Frank’s position as a receiver a minor component of the game plan. But he still managed to lead the team both of his years with 532 receiving yards, averaging 26.6 yards finishing with 20 career receptions, seven of those catches were for touchdowns. Frank was an all purpose player on the field. In addition to catching the ball, he blocked kicks and handled the kickoffs on special teams. When the team needed him, Frank became a threat on defense. In a game against Kansas, Frank’s big defensive play was the deciding factor in Colorado's one point victory.

At the end of the 1956 regular season, the Colorado Buffaloes were selected to play against the Clemson Tigers in the Orange Bowl in Miami on January 1, 1957. Like most southern football teams, Clemson wasn't integrated and vowed to boycott the bowl game if Clarke and Wooten took the field. Colorado’s head coach Dal Ward was relentless in his decision to play all of his players and did not back down, letting Clemson officials know that they would be there and hoped they would reconsider their discriminatory decision and play the game. Clemson finally agreed to play the game but Colorado faced another major discrimination problem. The team hotel, Bal Harbor Hotel located in Miami, would accommodate the Colorado team but Frank Clarke and John Wooten, the two African American players, were not welcomed to stay at the hotel. In a recent interview John Wooten said, "Miami Beach was still segregated and the hotel personnel plainly stated they didn't want any Negroes coming down there. When it became apparent that Colorado wasn't going to back down, the Bal Harbor Hotel tried to reach a compromise. They said that Frank and I would have to stay in the same room and it would be on the top floor of the hotel. We stood strong. When we went to Miami Beach, we had our usual roommates and it was business as usual. And Clemson did show up at the game and we beat them." Their 27-21 victory over Clemson was again marred by another example of the racism Frank faced throughout his career. The whites-only Indian Creek Country Club in Miami Beach was the host of the post-game celebration party. Upon the team’s arrival, the Orange Bowl committee insisted that Coach Ward asked Clarke and Wooten to leave the premises. Reluctantly, Coach Ward obliged and made arrangements with a prominent African American Miami doctor to host Frank and John at what was Miami’s version of the Cotton Club. The change of venue from the stuffy country club setting to a place where they were welcome was more fun for the African American teammates.

Frank’s team mate John Wooten

Clarke left Colorado after playing two seasons as their all-time leading receiver. He earned honorable mention All-Big 7 honors as a junior and was selected to play in the Copper Bowl All-Star game at the end of his senior year.

Frank Clarke was inducted into the Colorado University Athletic Hall of Fame on October 17, 2008.

Frank Clarke’s NFL career began when he was selected in the fifth round of the draft by the Cleveland Browns. On top of the pressure to win, the transition from college to the pros was mentally and physically noticed right away, but Frank never thought of quitting. A roommate to the future hall of famer, running back Jim Brown, Frank wanted to prove to Coach Paul Brown that he was a legitimate NFL player. He credits teammate Ray Renfro for encouraging and working with him when times got tough. With limited playing time Frank finished his career with the Cleveland Browns only catching ten passes during his three years.

Frank’s next move came in 1960 when the Dallas Cowboys, then called the “Rangers”, were a part of the NFL expansion plan, allowing the Cowboys to select 36 players from an expansion draft. The 12 NFL teams were allowed to protect 25 players from their 36-man roster. The Cowboys were then able to select three players from those unprotected by each team. Frank was left unprotected by the Cleveland Browns and was selected as a member of the first Dallas Cowboy team.

Now a part of the Dallas Cowboys, Frank was eager to improve his skills to become a top receiver in the league. He credits his success to the Cowboys veteran quarterback Eddie LeBaron and Coach Tom Landry, who worked with him on developing his route running and receiving techniques.

The following paragraphs are excerpts from an article written by Jim Franz, Sports Editor that appeared in the Legends of Sports-1995, a publication of The Beloit Daily News.

In 1961, Clarke said Landry called him into his motel room prior to an exhibition game. “We had a long talk,” Clarke said. “He explained to me how he hoped to build his team and how he wanted people around who could help it grow. He said he felt I had a lot of potential, but I would have to work hard to become what he thought I could. “That night I went out and had an outstanding game. What he told me helped a great deal. That conversation convinced me that he liked me for some reason. I knew that the rest was up to me.” Clarke was a wide receiver early in his Dallas career and had his best days at the position. In the opening game of the 1962 season, he grabbed 10 passes for 241 yards and three touchdowns in a 35-35 tie with the Washington Redskins. Through six games that season, he had caught 27 passes for 698 yards-a 25.9-yard average and scored 11 TD’s to lead the NFL in scoring. But when Bullet Bob Hayes came along, he moved to tight end. In 1964, the Cowboys picked up Buddy Dial and Tommy McDonald, two of the NFL’s better players, and Clarke was considered to be on the bubble. The 1964 season, however, turned out to be perhaps his best.

“That season I was a very consistent ballplayer,” he said. “I came up with a lot of third down catches. I blocked well. I had a nice flow going all season. And a nice harmony with the quarterbacks. And I was lucky. Luck, you know, always plays a part in an individual’s having a really good season. It was one of those situations of my being in the right place at the right time.”

Frank Clarke played his final NFL game at Lambeau Field in the famed 1967 "Ice Bowl" NFL championship game on December 31st. The game was played in brutal cold and windy conditions on a field that was frozen solid. The kickoff temperature in Green Bay was -13°F, with a wind chill of 36 below zero. Frank’s family sat in the stands amongst the nearly 51,000 bundled up fans to watch what would become one of the coldest games in NFL history. The Green Bay Packers scored the game-winning touchdown with 13 seconds remaining, clinching a third straight NFL Championship with the winning score of 21-17. Frank finished the game with 2 catches for 24 yards.

Frank Clarke, at the age of 33, was the last of the original Cowboys to retire.

As a Cowboy, he set numerous franchise records that held for decades. Frank played eight seasons with the Cowboys, and finished his NFL career with 291 receptions for 5,426 yards and 50 touchdowns. He was the first 1,000-yard receiver in franchise history, recording 1,043 yards in 1963, named All-Pro in 1964. Frank led the Cowboys in receiving yards and touchdown catches from 1961 to 1964, he still shares the franchise record for consecutive games with at least one touchdown catch (seven) with Bob Hayes, Terrell Owens and Dez Bryant. Frank’s 14 touchdown catches in 1962 set a franchise record that stood until 2007, when it was broken by Terrel Owens. He also held the Cowboys record for career receiving multi-touchdown games at nine, until it was broken by Dez Bryant in 2014.

Life after football took Frank from the field to the broadcasting booth. In 1968, he joined lead sports anchor Verne Lundquist for the sports segment on WFAA-TV Channel 8, every Saturday at 6:00 and 10:00 P.M. Lundquist found the ex-Cowboy pleasant, bright, handsome and very intelligent, the perfect man to be on the airwaves. With this position, Frank became the first African American sports TV anchor in Dallas. Channel 8 saw it as a win for the station to showcase a former high-profile Dallas Cowboy.

Frank’s broadcasting career led him to becoming the first African American CBS analyst from 1969-1973, working alongside famed broadcasters Frank Gifford, Pat Summerall and Don Criqui.

Frank’s life after football also found him involved in a number of programs that served the youth and underprivileged in Dallas. City officials knew him to be a leader who worked quietly behind the scenes to improve the plight of minorities around Dallas. Frank served as coordinator of the city’s Council for Youth Opportunities at the request of then Mayor Erik Jonsson in1968, running programs that served thousands of Dallas youths.

Frank Clarke at the opening of an East Dallas recreation center in 1968.

Photo by Jack Beers-The Dallas Morning News

Beloit’s Franklin “Frank” Delano Clarke passed away on July 26, 2018 at the age of 84 in McKinney, Texas.

William “Bill” McCrary

William “Bill” McCrary was born in Beloit on Nov. 5, 1929. His mother died shortly after giving birth and he was adopted as an infant by William "Bud' McCrary and Estella Kidd-McCrary, a family friend, who raised him as their son. Growing up in the Edgewater Flats and playing “sandlot” baseball, Bill displayed his baseball potential at an early age. Baseball was a big deal in the African American community as far back as the late 1920’s. Beloit had segregated teams back then, the white teams played at Summit Field on the east side of town and the African American players played at Edgewater Park also known as “Grady’s Field.” Bill was surrounded by men that loved the game and played it well.

When he was 12, neighbor Lonnie Edwards told a young McCrary that he “was going to make a baseball player out of him.” Harry Pohlman, coach for Beloit American Legion baseball, scouted McCrary while he was a student at Lincoln Junior High School to play on his team. Pohlman’s recruiting of the 16-year-old in 1946 paid off, as McCrary joined the team becoming the only black player. “Coach Pohlman was one of the best teachers I ever had when it came to the fundamentals and playing Legion ball was my first experience with white ballplayers,” McCrary said. Beloit High School did not have a baseball team until 1953 so legion baseball was the only avenue of organized baseball that McCrary was able to hone his baseball skills. He credits Coach Pohlman for his success leading up to joining the Negro League.

“The St. Louis Cardinals were having a tryout in Beloit when I was 17,” McCrary said. “That was 1946. Mr. Pohlman asked if I was going and I told him I wasn’t because they weren’t taking black players back then. Why waste my time? He came over to my house and made me get on my bike and ride over to the tryout. He followed me in his car.”

“There were about 50 players and I was the only black. After the tryout was over they called everybody to the center of the diamond. I just got on my bike and pedaled home. I didn’t see why I should stick around. At 6 that night we got a knock on the door and it was Mr. Pohlman and the Cardinals scout and they wanted to speak to me and my dad. They asked me if I wanted to play baseball.”

“The scout told me I was the most talented player at the tryout. He wanted to take me to St. Louis, but he couldn’t do that. So he told me he’d help send me to a really good team in the Negro League.”

In 1946 there were no Major League teams accepting black ballplayers, so Clifton “Runt” Marr, the St. Louis Cardinals’ scout who came to McCrary’s house arranged a tryout with the Kansas City Monarchs, a Negro League in Missouri. The Monarchs liked what they saw in Bill McCrary and after a week of trying out they offered him a contract.

Bill gave pause when the Monarchs instructed him to go find a room at the Streets Hotel, a hotel owned by the Monarchs’ owner James L. Wilkinson. “But I told them I couldn’t stay. My dad would kill me if I didn’t go back and graduate high school. So they let me go back to school and then come back when I was done.”

William McCrary’s 1948 high school graduation picture.

After graduating from Beloit High School, McCray joined his new team the Monarchs in Kansas City, Missouri. There he found himself playing with or against other Negro League players like Josh Gibson, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Buck O’Neil and Leroy “Satchel” Paige.

It was Satchel Paige that gave Bill McCrary the nickname “YoungBlood,” a name that stuck with him for the remainder of his life. Growing up in Beloit, McCrary was known as “Bootch”. He didn’t know who gave the nickname to him, or why. He was proud of his new nickname, “Youngblood” especially because it came from Satchel. McCrary tells the story that when he made the Monarchs, Satchel Paige called all the teammates together and said, “Now we have some young blood.” Pretty soon everyone was calling him “Youngblood.”

The much younger McCrary bonded with the much older Paige, who treated him like a son and took him under his wing. Satchel would pick him up at the hotel and go out for breakfast. In their spare time they would go to play pool at the billiard hall. McCrary admired Satchel Paige and was very thankful for their friendship. He learned so much about baseball, how to get along with people and life, things a young 17-year-old needed.

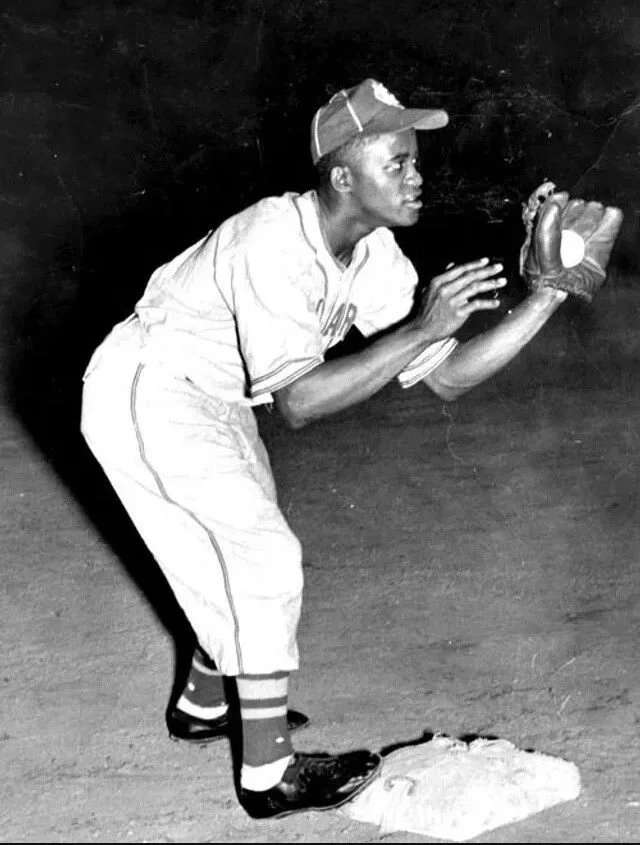

Bill “Youngblood” McCrary, at 5-foot-10, 175-pounds was a backup his first season with the Monarchs in 1946. The following two years he played shortstop, batting .341 lifetime as a player with the Monarchs.

McCrary missed playing with Jackie Robinson who had played for the Monarchs in 1945. Robinson had already headed to the Brooklyn Dodgers farm team, later becoming the first African American baseball player to play in the Major Leagues.

In the off-season, McCrary played for the barnstorming Satchel Paige All-Stars to earn extra money. The most McCrary earned playing ball was $850 a month. That was a lot of money for a young “negro” ballplayer in those days.

Bill McCrary left the Kansas City Monarchs in 1948 with hopes of playing in the Major Leagues. He joined the Fargo Morehead Twins, a farm team in Fargo, North Dakota. McCrary played on several other farm teams including the Janesville Cubs, a D League team affiliated with the Chicago Cubs as well as with the semi-pro Omaha Rockets. You could also find him showing off his baseball skills on other regional baseball teams, often earning spots on their all-star rosters.

On June 25, 2016, the Milwaukee Brewers honored the Negro Leagues by paying tribute to William McCrary, Ray Knox and Roosevelt Jackson. McCrary graced the cover of the game day program pictured above.

McCrary stands with his framed picture that hangs in the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

William McCrary’s professional baseball career with the Monarch’s was a childhood dream come true. His time spent with the team traveling, meeting and playing against some of the best negro baseball time of that era created lifetime memories. Cherished scrapbooks full of pictures and articles that chronicled his journey was something he was proud of and enjoyed sharing with others.

McCrary was a big supporter of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum that is located in Kansas City, MO. He often attended Negro League reunions and other events where he and others enjoyed reminiscing about the good old days, signing autographs and posing for pictures.

William “Bootch, Youngblood” McCrary, was inducted into the Beloit Historical Society’s Sports Hall of Fame on June 5th, 2014. In the book, “A Legend Among Us, The Story of William “Youngblood” McCrary” written by Linda Pennington Black, McCrary said, “That night was one of the happiest, and proudest moments in my baseball history. The feeling of exhilaration and pride overwhelmed me, as I spoke to a group at the high school. It was just a moment I couldn’t believe, and never thought I would live to see.”

McCrary has no regrets of playing in the Negro League during a time when he personally faced segrgation and Jim Crow laws. He was thankful for his coaches that stood up to the restaurants and hotels that refused to serve him a meal or were against providing lodging for him because of the color of his skin. McCrary even faced racism when he played regionally near his hometown of Beloit, but never let it get under his skin. Looking back over his life, playing baseball presented him with the happiest moments of his life.

William “Bill” McCrary passed away July 21, 2018 in Hot Springs Village, Arkansas at the age of 88.

Carolyn Bolton

It was not until 1954 that the Beloit Public School hired Mrs. Carolyn Bolton, their first African American teacher. Many of her students that are still alive remember her fondly.

Carolyn Bolton was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee where she attended Howard High School. After graduating from high school, she sought to continue her education and enrolled at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) in Atlanta, Georgia. Carolyn went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in Political Science, in Atlanta, GA. During her time at Clark, she met a student named Clarence Bolton and they married shortly after Carolyn graduated.

In 1953, Carolyn and Clarence moved to Beloit, Wisconsin. Carolyn applied and was hired by the Beloit Public School system, becoming the first African American teacher ever hired by the school system.

Mrs. Bolton taught fourth grade at Strong School and fifth grade at Wright School. She recalled, “In my first class there were 38 students and only 8 of the students were ‘negro’,” using the 1950’s-era term for African Americans. For Carolyn, race did not matter, as she poured her energies into applying innovative methods and excellence to reach and teach each child, encouraging them to do their best.

As a classroom teacher, Carolyn’s desire to broaden her education continued at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater where she completed a master’s degree in counseling and guidance, as well as completing post-graduate extension courses through UW-Madison. After many years in the classroom, Mrs. Bolton became Beloit Public Schools’ first African American guidance counselor and was assigned to work with students at Beloit Memorial High School.

At the end of the 1973 school year, the Boltons left Beloit and moved to Milwaukee. Carolyn’s career as a guidance counselor continued as she began working for Milwaukee Public Schools. She retired as an educator in 1981, but has continued to mentor young people through her various community involvements.

Through the years, Carolyn has earned numerous awards. She was recognized by the Wisconsin Educators as one of Wisconsin’s top teachers, and received an all-expense paid trip to New York for the national convention.

Carolyn and her husband Clarence were married for 57 years. They raised four children, Clarence passed away in 2004.

Boredom never entered Carolyn’s life. She kept busy serving on various foundation boards, singing in her church choir, quilting, gardening and was involved with the Milwaukee Symphony League.

In her late 70’s Carolyn became an entrepreneur starting a small business called, “Cards By Carolyn.” She made all-occasion note cards using fabric purchased from all over the world, donating the proceeds to support a variety of charitable organizations.

Carolyn Smith Bolton is a golden soror of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. She has been a member for more than 70 years and in 2014, the sorority recognized her for long-time service and dedication.

Carolyn Bolton, now in her 90’s, opened the classroom door for other African Americans teachers in the Beloit Public School system. It would not be until 1960, six years later, that the school system would hire two more African American teachers.

Joe Lomax

Below is an adaptation from Joe’s written account entitled

“Memories of the First Black Police Officer in Beloit”

The Application Process

After graduating from college in 1963, Joe applied to become a police officer at the Beloit Police Department in Beloit. At that time, the police department consisted of approximately 65 predominately Catholic white officers, only two of whom had college degrees. Many had been hired because of their military experience. The police chief conducted Joe’s initial interviews and background check, especially on his family. It was as if the chief went beyond the usual hiring process with Joe by taking time to inquire about his affiliation with black church ministers and other black people he felt might have put Joe up to applying to join the Beloit Police force. Joe passed all the related exams presented to him with flying colors. Weeks later after all the exams and background checks were completed, Joe was invited into the chief’s office. At that meeting the chief slapped Joe’s file down on his desk and asked a few questions about people who were used as references and then said, “either you’re a good guy or these are a bunch of damn good liars, because I couldn’t find anything wrong with you!” Joe left that meeting feeling a strange mix of satisfaction and insult. There was a rumor in the black community that Beloit’s current police chief had sworn that there would never be a black officer on the department as long as he was chief, and this was not the exact language he used to express his displeasure with hiring a black person. For Joe’s next meeting the chief requested that his wife, Kathryn, accompany him and be questioned as part of the hiring interview. He believed that this was the first time a wife had been included in the hiring process. Several weeks later Joe was summoned to meet the newly appointed police chief, the former chief who had sworn he’d never have a black officer on the department, had retired. The new chief assured Joe that he would have full law enforcement authority for the entire city and not be a special deputy assigned only to the black community and black functions, which was his main concern. With the word of the chief, he signed on and was hired. Joe was informed that the probation period had been extender from six months to one year. Why was the probation period changed? Nothing was going to deter him from reaching his goal of becoming a Beloit police officer.

Pictured is Joe preparing for his interview in 2010 for the documentary, Through Their Eyes: The History of African Americans in Beloit, Wisconsin From 1836-1970.

Getting Started

Joe went through a short law enforcement training academy. Because of his excellent note taking and comprehensive notebook he had compiled, his notebook was selected to be sent to other agencies and programs as an example of the quality of the Beloit Police Academy. Joe received his uniform along with equipment and was assigned to work all three shifts, 7-3, 3-11 and 11-7 during his probation period. His first assignment was to work day shift and walk the beat downtown. Believing this was for the purpose of exposure to the city of Beloit that we now having a uniformed black police Joe was honked at, called names, stared and sneered at by people and drivers even circled the block to confirm what they saw. He recalls that a few copper pennies were tossed his way. Most of this was done by white citizens, while a few black people smiled and shook their heads in approval. There were other blacks that looked at him with suspicion and distain. Joe realized that he was going to have to earn approval from both sides, a challenge that remained with him throughout his first year.

Changes He Faced

It didn’t take Joe long before he discovered that officers had the discretion to give breaks if they felt they could get compliance without formally charging, ticketing or arresting a person. It was evident that the persons receiving most of the breaks were affluent, well known, influential and well connected. Few if any blacks met the criteria and received similar breaks. Joe soon became aware of the tremendous authority and power police had over citizens. Having grown up in the black community of Beloit Joe knew a lot about what went on, who played the number and where folks gambled with cards, dice or other games. After finding that there were similar activities going on in the white neighborhoods and even some officers played poker for money, Joe decided unless it happened in front of him or was related to an incident, the past would remain the past and wouldn’t deal with it.

Wearing the uniform and becoming known as a police officer changed the way people interacted with Joe in the black community. While some thought it was about time, happy and supportive, others felt threatened and made comments like, “look at him, he thinks he’s so damn special. I’ll tell you one thing, he better not try to arrest me.” Except for Joe’s family and very close friends his presence at gatherings or parties changed the dynamics of festive events. Within minutes of his arrival the whole group knew that Joe the cop was there. He didn’t feel comfortable breaking loose and having a good time, a loss that came with the job of being a Beloit Police officer.

Exposure to a Different Beloit

Having grown up in Beloit, Joe thought he knew the city pretty well. He soon found out he didn’t know all the businesses, taverns, clubs, streets, areas and the different levels of living. He had to study the Beloit map, city directory and memorize roads, streets and lanes not only would this be part of his evaluation but calls for assistance in an officer’s area had to be responded to in a reasonable period of time. Joe’s response to calls in different areas exposed him to a range of living levels from ankle deep carpet to dirt floors. He entered sterile homes to houses where roaches crunched under his feet like peanut shells or periodically dropped from the ceiling to his uniform. He found that both the wealthy and the poor have issues requiring police intervention but additional care was taken with the former.

Street Patrol and Inspections

Part of Joe’s responsibility of walking the beat was to check businesses, hotels, theaters and taverns in and around the downtown area. Many of these establishments, especially the taverns had never welcome or allowed a black person inside let alone a black person with authority to conduct an inspection and evaluate the operation. Joe’s first inspection of a tavern was around 11:30 a.m., he was met with a customer saying, “hey, what the hell is he doing in here?” Fortunately, the bartender told the patron to calm down and announced that Joe was the new cop in Beloit. This type of hostile reception repeated itself many times that year and occasionally Joe felt he had to unsnap is weapon. A few months later he would have to inspect a place on his patrol beat that had been infamous for restricting access to black high school students. It was the popular white teen hangout called the “Pop House.” You can only imagine the look on the owner’s face when Joe walked in to check the place out.

Mobile Patrol Duty

On Joe’s first day in a squad car, his assigned field training officer gave him three basic rules to follow. First, never touch his squad car steering wheel intending to drive. Second, they get coffee before the supervisor comes out. Third, we make just as much money if we do nothing as we do if we go looking for something to get involved in. These were three easy rules to remember but differed considerable from the law enforcement training that he had been taught which was to look for the unusual and/or suspicious and check it out. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the way the field officer saw it. After riding with a number of officers, Joe was assigned to parking patrol, given a motorcycle and taught the ticketing route that had been used for years. Joe’s first independent run of the route drew complaints from individuals and businesses along the route. He was given an assignment of ticketing vehicles parked in an alley downtown because they were in violation of the city fire ordinance. Joe issued some twenty tickets not knowing that these vehicles had been allowed to park there for years. As expected, people called the chief and some even drove to the police department to complain about Joe giving them tickets. Because these vehicles were in violation the chief supported his action. When it was over Joe had a feeling that he was set up by the person who assigned him the task of issuing those parking tickets. As a result, many in the downtown businesses adopted a negative attitude towards him, when they saw him walking down the block, people would run out and put money in all the meters on the entire block. This was good for customer service and the city treasury, but was an open display of their disapproval of Joe issuing tickets.

Coping with Racism

Right from the start, some officers expressed a request not to be paired with Joe or have him as their patrol partner. Given their attitudes toward black people in Beloit, this was probably a good thing. Joe was viewed as an intruder, there were a number of times when comments or the behavior of the white officers would slip into conversation either directly, in jokes through insinuation or through the treatment of black people. It was not uncommon for a white officer to use the n-word and then apologize to Joe and let him know he was not talking about him. Joe complained to the chief and to his credit sent out a memo for officers to cease with jokes and other antics that tended to promote and perpetuate situations. This did not eliminate the behavior but did immediately reduce the overt use of jokes and other blatant expressions in the station. There were times when officers would talk with black people in a manner similar to that of a plantation owner to a slave, regardless of the age or status of the black person. Realistically, there were only a few special officers that earnestly shared laughter and mutual acceptance and/or respect for black citizens. Joe was able to see firsthand the relationship and influence of political and financial clout in obtaining warnings and the benefit of the doubt whereas black folks without financial means got the short end of the stick. When riding with a white officer there were times when some white folks argued that they didn’t want Joe to handle their complaint.

Being Tested

Joe encountered several tests during his first days. While out on driving his parking route, he spotted a car that was parked in a no parking zone. Joe pulled behind it and wrote a parking ticket, just as he finished placing the ticket on the windshield, a young, well dressed white women came out and stated that was her car. She approached Joe and asked him if there wasn’t some way she could get me to take the ticket back. He advised her that since he had placed the ticket on the car she would have to take it to the station and make her appeal to have it dismissed. She smiled, started acting coy and said she would just as soon avoid that if there was some way the two of them could work it out and Joe told her there was not. As she turned and started to walk away, he realized that he had forgotten to date the ticket and called her back to put the appropriate date on the ticket. As Joe drove off he noticed the supervisor observing from his squad car about a half block ahead, he realized then that this had not happened by accident, this was a set up.

Another test came when Joe was working second shift. There was a disturbance at a black tavern in which another squad car had already arrived at the scene. When Joe and a senior officer arrived at the bar too, the patrons were yelling and verbally challenging each other. Suddenly the all the officers looked at him like, “these are your people, why don’t you handle it?” Joe didn’t have a clue as to what had happened before he arrived, so he said the original responders should handle it. He was summoned to the supervisor’s office and asked why he had not taken an action but the supervisor couldn’t chew Joe our because there were five officers on the scene with more seniority.

Success?

At the end of Joe’s year of probation, the chief called him and the night shift captain to his office. The chief personally congratulated him for successfully completing the probationary period. As the captain and an elated Joe were leaving the office the night shift captain said, “Well, I guess since the chief already said you passed probation, I guess I have to sign the certificate,” and walked away. The captain’s very negative comment immediately turned a happy occasion into one of disappointment and anger. Joe left thinking, “I’ll just be damned!”

Joe Lomax worked hard to become a good police officer and a specialist in traffic. Eventually, because of his knowledge of traffic, officers with traffic questions started to rely on him for answers to their questions. He saw this as the first step towards acceptance within the Beloit Police Department. Racial animosity, however, became even clearer two years later when Joe attended Northwestern University Traffic Institute in Evanston, Illinois. As one of the top achievers in the class, he received verbal offers from other departments like Arizona State Patrol. At the graduation ceremony, the Beloit chief of police appeared on stage and announced a special presentation. He then called Joe to the staged and awarded him with sergeant stripes and a promotion to supervisor. This gesture did not sit well within the department, at least two or more officers resigned because of it and some officers had vowed that they would not take orders from him even though he was their supervisor. Once again to the police chief assured them that they would take orders or would not be working for the Beloit Police Department.

My Companion During the Journey

“I cannot give enough credit to my wife, Kathryn (Byrd) Lomax, for her love, tolerance, and support during my venture into law enforcement. My struggle changed her life as well. She was the one who had to deal with my mood swings, anger, silence, frustration, fears, and disappointment. Because I had to be ever vigilant of my behavior, confidential issues, investigation of gross incidents, and those who would have me fail, Kathy became the sanctuary I could count on in times of turbulence. In addition to being my refuge from external pressures of the job, she took care of our children and provided companionship, food, quiet, and the time I needed to be effective on the job. I cannot imagine having succeeded without her support.”

Joe and his wife Kathy

Leaving the Police Force

Joe B. Lomax left the Beloit Police Department in 1969 to help develop the Police Science/Criminal Justice program at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. In 1972, Joe earned his Master of Arts degree at University of Wisconsin-Platteville, he became the first black professor at this predominately white university. A scholarship was established in Joe’s name at UW-Platteville, the Joe Lomax Criminal Justice Scholarship, was established to honor Professor Lomax for his service in helping develop the Criminal Justice program. He taught at the university for 38 years, during his tenure, he served as adviser to the student Criminal Justice Association, established the Criminal Justice Career Day, Internship program, CJ Advisory Board, Law Enforcement Training Academy, Employment Search Workshop, and initiated the Criminal Justice Master of Science and undergraduate online programs, Forensic Investigations, and Racial Disparity in Criminal Justice and Education Task Force.

About Joe Lomax

Joseph Ben Lomax, the son of Joseph A. and Ben Theresa Lomax, was born on April 25, 1939. A 1957 graduate of Beloit Memorial High School, Joe excelled in academics as well as athletics. He earned major awards and letters throughout his athletic career.

Joe’s 1957 Beloit Memorial High School graduation photo.

In high school Joe excelled in football, wrestling and track.

Joe was a fixture at Turtle Creek Swimming Pool during the summer months where he worked as a life guard.

Pictured: Joe (right) and fellow lifeguard Robert House

Pictured: In the 1950’s Joe (center), John Payne and Ocie Peterson (manager of Turtle Creek Swimming Pool)

After graduating from high school, Joe continued his education in the state of Colorado at Trinidad Junior College and finished at University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point with his Bachelor of Science degree in 1963. In 2016 Joe was inducted into the Beloit Memorial High School Hall of Fame. A plaque with his name is permanently placed in the school’s Hallway of Fame.

Joe and his wife Kathryn (Byrd) are the parents of four children, Yvonne, McLane, Suzanne and Michael.

Photos courtesy of Joe Lomax, Oscar Bond, Beloit Daily News and Book of Beloit Vol. II - Gloria Peterson Vance

Walter Knight

Walter Knight’s rise to the top in the political arena didn’t come easy. He went from working in the foundry at Fairbanks Morse to being elected the first African American member of the Beloit City Council.

Born in Arkansas in 1933, Walter Knight moved to Beloit in 1951 after graduating from high school. Shortly after arriving Knight began working in the foundry at Fairbanks Morse. Working in the foundry he endured grueling heat and unbearable conditions. During that time those were the jobs African Americans held, many described the conditions as hot, dirty and smoky. Water Knight knew this was not what he had envisioned for his future, so determined to better his position at work he enrolled in vocational school. Knight continued working in the foundry for a few more years and eventually worked his way up to a more skilled position in the machine shop at Fairbanks Morse.

In the early 1960s Walter Knight’s appointment in the foundry as a Union steward lead him to run for a seat on the Grievance Committee. The Grievance Committee comprised of ten officers that represented various areas of the plant. In an interview for the documentary Through Their Eyes; The History of African Americans in Beloit, Wisconsin From 1836-1970, Walter Knight recalled that there were about 5,000 employees that worked at Fairbanks Morse and 10% were African Americans.

It was after Walter had served as union steward for a few years that he decided to run for the office of Grievance Committee Men and won one of the ten committee positions. His union involvement at Fairbanks Morse in the early 1960’s gradually led him to be elected Vice-President of Local Union 1533 United Steelworkers of America AFL-CIO. Walter added another accomplishment to the list, as he applied for and was granted a high security assignment for Fairbank’s government atomic energy project.

Walter Knight was quite active in various community groups in the city of Beloit. The Black Resource Personnel group, a community activist organization, wanted to support one of their own members as a minority candidate for one of the vacancies on the Beloit City Council in the upcoming election. They chose Walter Knight. There were 13 candidates running for the four open seats on the Beloit City Council. In 1972, Walter Knight made history when he was elected as the first African-American to serve on the Beloit City Council. He served 13 consecutive years with terms as vice-president and 2 terms as president of the council.

While fulfilling his duties as a newly elected councilman for the city of Beloit, Walter continued as Vice-President of the Union, but he had his eyes set on a more ambitious role in the Union organization. In 1973, he ran for the presidency of the Local Union 1533 United Steelworkers of America AFL-CIO at Fairbanks Morse against the incumbent of 9 years. Walter Knight, even after three recounts, won by nine votes. He was elected President of Local Union 1533, serving as the Local’s second black president.

Walter Knight worked for Fairbanks Morse for 25 years from 1951-1976 in several different roles from Community Relations Representative, Machinist, Personnel and Employee Relations.

In 1976 Walter Knight and The Black Resource Personnel group was approached to assist in the planning and formation of an organization called the Opportunities Industrialization Center for Rock County. The OIC provided employment training, job placement, educational resources and other services. Mr. Knight worked closely with Fairbanks Morse and other companies in Beloit to train approximately 3,000 adults and 3,000 youth for employment with over 80 percent of the adults finding employment after training. Mr. Knight served as the executive director of OIC for over 30 years, making a significant impact on the city of Beloit. OIC closed its doors in 2010.

Walter Knight, a young man who came to Beloit after graduating from high school in 1951, left an indelible mark on the city in numerous ways. He worked in the trenches, provided leadership that was sorely needed and created opportunities for the minority community in Beloit. He provided a powerful voice for activism in a very unassuming way, a perfect example of strength in humility.

Mr. Knight served as secretary and chairman of the Police and Fire Commission and on a variety of ad-hoc committees. He also served as chairman of the Governor’s Committee on Minority Business Development, President of the Beloit Breakfast Optimist Club International, and on the National Human Resources Committee – National League of Cities-Washington, D.C. Walter Knight has served and supported the community in many other various religious, civic, cultural, and educational aspects of our community.

On Saturday June 22, 2019, as part of Beloit’s Juneteenth Celebration, the Portland Avenue bridge was honorably named the “Walter R. Knight Bridge.” The city of Beloit joined in the unveiling and ribbon cutting celebration of a bridge named after Walter Knight, an African American trailblazer in Beloit.

George Hilliard

George Washington Hilliard was born on February 7, 1915 in Pontotoc County, Mississippi in the small town of Toccopola. The family moved to Beloit within a five period because the 1920 United States Census has the Hilliard’s living in Beloit, on Athletic Ave. The household included George’s parents George Sr. and Hattie, sister Fanny, brother Nimrod, his grandmother Fannie Moore and a male lodger. George’s mother Hattie Moore Hilliard died in February 1921 and is buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Beloit, she was only 27 or 28 years old. The 1930 United States Census finds the family still residing at 1402 Athletic Ave. but George Sr. is now married to a woman named Leila. The household still includes George, his siblings Fanny, Nimrod and their maternal grandmother Fanny (Fannie) Moore.

George was involved in teen activities such as the Edgewater Flats Hi-Y, Boy Scouts and he was a member of Second Emmanuel Baptist Church, now known as Emmanuel Baptist Church. His father, George Hilliard Sr.’s name appears on the Certificate of Incorporation for Second Emmanuel Baptist Church, dated June 3, 1927, where he served as a deacon.

Young George excelled in school, ranking in the top third of his class at Beloit High. He not only excelled in the classroom, he also starred on the football conference championship team his senior year.

Beloit High School Principal, J. H. McNeel who described George Hilliard as being “a deserving young man,” recommended him to the Beloit College admissions department. George received a scholarship from Beloit College and began his freshman year in the fall of 1932 majoring in chemistry. He was the consummate student-athlete who successfully mastered his studies and play football for the Beloit College Buccaneers and graduate in four years.

Beloit College had enrolled African Americans long before George became a student in 1932. Although they participated in sports and maybe a class club, African Americans did not live in the dormitories, engage in social activities, nor join fraternities or sororities.

As a student George, unfortunately was a part of a media cover up. In 1935, photographs were taken in Pearson Hall of Science of students at their desk and you can see George, standing at a lab table. The photographs were taken to capture academic life for several Beloit College publications. When this particular photograph from the science lab was published, not only was the unsightly spot on the ceiling airbrushed out so was George Hilliard. Typical of the time, Beloit College did not want to show an African American student in a brochure being viewed by prospective white parents who were considering sending their child to this institution of higher learning.

George continued his postgraduate education training in thoracic/chest surgery at Howard University Medical School and Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. He also studied gynecology and pulmonary surgery. Upon completing his surgical residency, many African Americans were hopeful that he would set up a practice in his hometown of Beloit, instead George moved to Milwaukee in 1951.

Even though George was highly qualified he was not allowed surgical privileges at any of the major hospitals in Milwaukee when he first arrived. In 1955 George was still fighting for the right and the admittance of any doctor to practice medicine and surgery in any Milwaukee hospital regardless of race. Dr. George Hilliard built a medical practice specializing in pulmonary surgery at 4th and North Ave, he also made house calls during the influenza epidemic that hit worldwide in the 1950’s. Dr. Hilliard later joined the staff at Mercy Hospital, one of the few hospitals in Milwaukee where African American doctors could practice.

Dr. George Hilliard brought honor to his profession by serving as a delegate to the Wisconsin State Medical Society for ten years. He served for one term as the treasurer of the Milwaukee County Medical Society. He was a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, a member of the American Federation for Clinical Research, a member of the American Medical Association and the National Black Medical Association.

Dr. Hilliard was actively involved in the city of Milwaukee. He served on the Milwaukee Commission of Community Relations, especially during turbulent times when racial tensions were high. The Milwaukee NAACP, Boys Club and the Milwaukee Urban League were organizations in which Dr. Hilliard passionately invested his time and energy.

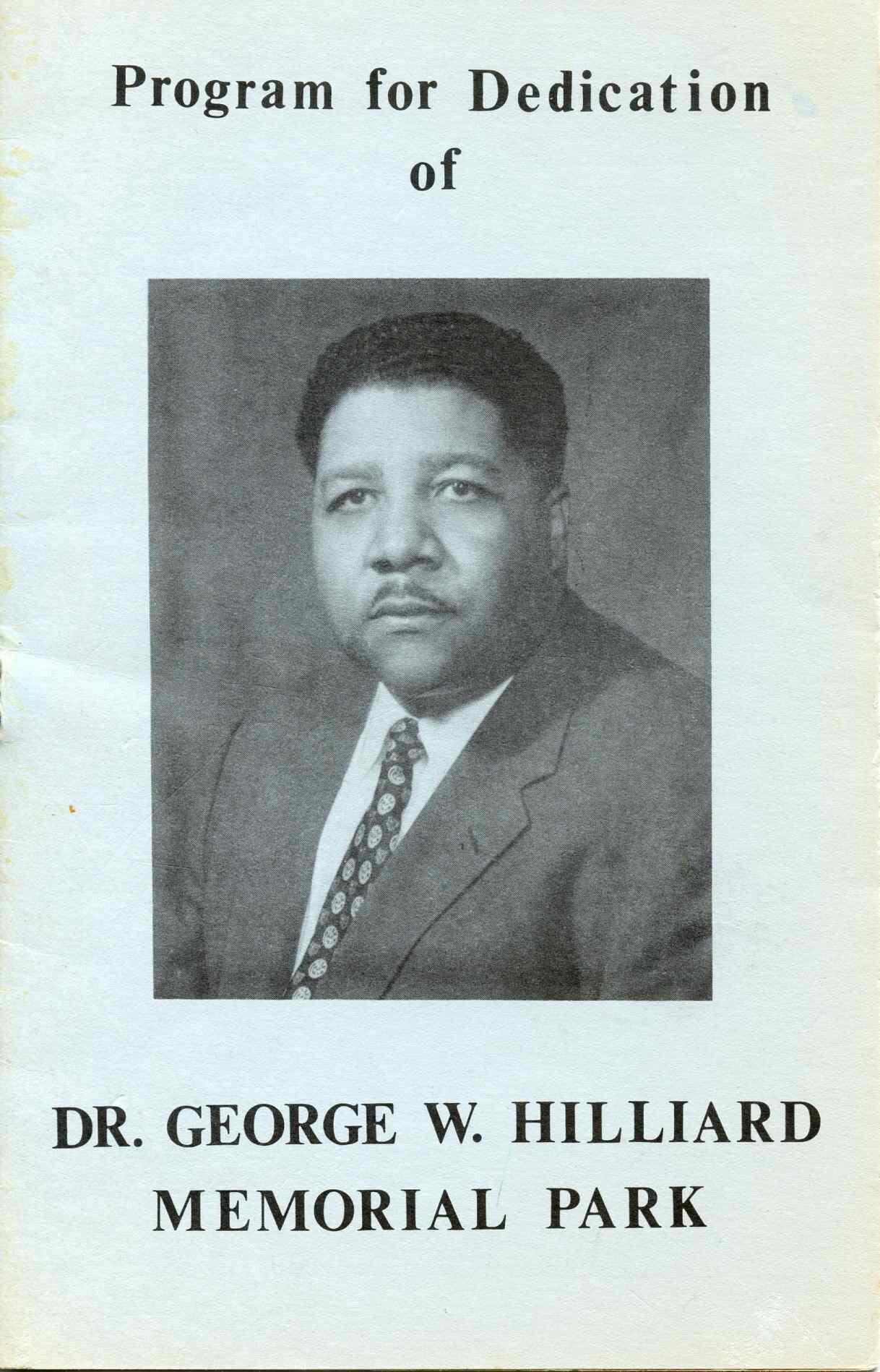

Dr. George Washington Hilliard Jr. passed away on April 8, 1969. A Beloit College Bulletin obituary described him as “a prominent surgeon and Negro community leader.”

Beloit dedicated a park in his name on Labor Day in 1976, an honor many African Americans felt was well-deserved. The Dr. George W. Hilliard Memorial Park is located at 1443 Athletic Ave, a short walk from Dr. Hilliard’s childhood home. In the park dedication program, Dr. Hilliard was described as “an avid student of medicine, an excellent teacher within his own profession and a person with great understanding and love for his fellow man.”

Dr. George Hilliard was inducted into the Beloit Historical Society Hall of Fame in 1981.

Irma Bradford

Irma Black Bradford, was born and raised in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, but now calls Beloit home. It was during her senior year in high school that conversation between her teachers and her parents began about Irma’s recruitment to play basketball for a semi-pro team. As a point guard, she was considered a talented high school basketball player who could shoot, dribble and handle the basketball. Irma’s parents gave permission for her to join a barnstorming basketball team called the “New York Harlem Chic’s” in 1959 after graduating from high school.

The team was owned and managed by a man from Beloit named, Dempsey Hovland. He chose Beloit for the location of the team’s headquarters. Segregation was widespread in our country at this time and Hovland was someone who advocated for minorities to have an equal opportunity to participate in sports, especially women. He managed an all-white women’s team called the Texas Cowgirls; the New York Harlem Chic’s was his first all-women’s African American team.

Irma had never heard of the city of Beloit, but was excited about an opportunity to continue to play a game she loved. Upon arriving in Beloit, Irma remembers staying at the Hobson Hotel or the Marvin Hotel and eating meals at the Hobson Club. In 1959 these were probably the only places in Beloit where a group of African American women’s basketball players could find lodging and meals. After several months of practice, Irma and her teammates were ready to start their inaugural season as the New York Harlem Chic’s.

The team packed their belongings along with their basketball equipment into a station wagon and sat out on their barnstorming tour. Some of the states they travelled to for games were Minnesota, Nebraska, the Dakotas and they even went as far as the state of Washington. Irma remembers staying in nice hotels, being well-received by the town’s spectators and treated like celebrities. She recalls the excitement of traveling from city to city enjoying the competition and sometimes playing two games in one day. The New York Harlem Chic’s were at times matched up to play men’s basketball teams, which was definitely a challenge. The Chic’s showed off their skills as serious basketball players but also added some fun entertainment for the fans in attendance. Despite traveling crammed in a vehicle for weeks at a time, Irma said “it was good fun and it gave me an opportunity to meet some wonderful people.”

By no means did they become rich. Irma and her teammates were paid weekly, the agreement was that their room and board was paid for, but they were responsible for providing their own meals. Eating out in restaurants became costly so they purchased a hotplate and occasionally cooked in their rooms.

Irma played only one season with the New York Harlem Chic’s, she returned home to Tennessee and enrolled at Tennessee State University. During her time in Beloit she met a young man who captured her heart, LaVerne Bradford. Irma left Tennessee State University and traveled back to the city of Beloit where they were married on July 26, 1962.

When Irma reflects back over her basketball career, there are a couple highlights and memories that stand out more than others. She has very fond memories that go all the way back to her high school basketball career. Irma recalls when she played against Wilma Rudolph, known to Irma as “Skeeter”, who played at a high school located in Clarksville, Tennessee. Irma’s team always played well in the state tournament until they faced Wilma’s team, which would knock them out of the championship every year. This is a memory that still makes Irma smile, knowing that she played against Wilma Rudolph, who went on to become one of the greatest African American Olympic champions in track and field.

There is another lasting memory for Irma, this one began when she became a New York Harlem Chic’s player. She met her life-long friend, teammate Marva Towles. Marva, a star basketball player from Virginia, left her home and joined the New York Harlem Chic’s at the same time as Irma. Marva finished playing basketball and returned home to Virginia. She eventually decided to move to Beloit, found work and their friendship continued for years.

Irma currently resides in Beloit where she is well loved by the entire community.

Johnny Watts

Some of the most talented and remembered athletes to play sports in the State of Wisconsin were from the African American community of Beloit. These young men were ahead of their times. All agree that with the opportunities our athletes enjoy today, every one of Beloit’s sports heroes of yesterday would have been well-positioned for a shot in the professional ranks of their sport.

Johnny Watts, a 1986 Beloit Hall of Famer, blazed the trail for African American Athletes. Born John Wesley Watts on September 5, 1912, Johnny moved from New Albany, Mississippi sometime after 1920 to Beloit, Wisconsin where he lived with his grandparents Andrew and Lou Scott. Joining Johnny in the move to Beloit were his sisters Ethel Mae and Lula Belle. The 1930 United States Census listed the family living at the Edgewater Flats, Apartment 22.

Pictured is Johnny’s grandmother Lou Scott, sister Ethel Mae (back row), sister Lula Belle (front left) and Johnny on the right.

By Johnny’s sophomore year at Beloit High School, he had become undoubtedly a phenomenal basketball player, landing him a starting position on the varsity. “It was really something back then,” Watts said on the eve of his induction into the Beloit Hall of Fame. “All of the guys on the team had grown up together. Three of us had played together since junior high. In 1932, the talented Watts’ helped lead the Beloit Purple to their very first Wisconsin state title. His outstanding performance earned him the honor of being named to the All-Tournament team which at that time doubled as the All-State team.

Beloit High 1932 State Championship team, the first school to win three consecutive WIAA championships, from 1932-1934. Johnny Watts is the first African-American to play a starring role in the state tourney.

Under the helm of their new coach, Herman “Jake” Jacobson, Watts and his teammates had their eyes fixed on another state title. The team finished the Big Eight conference undefeated, a loss to Freeport, 25-23 denied Beloit an undefeated season. It was during the second game of the state tournament that Watts’ dreams of a repeat title came to a halt. An undercut from an opposing player caused Johnny to fall, bracing himself as he hit the floor it resulted in a broken wrist in the opening round. Beloit went on without Watts playing well enough to reach the finals of the 1933 State Championship against Wausau. With Beloit trailing in the fourth quarter, Coach Jacobson team needed a spark, and he knew exactly what his team needed. The moment was captured by Beloit Daily New Sports Editor Jack Clarke when he wrote, “While the wild cheers of 3,500 frantic customers roared through the field house, Johnny tore out on the floor.” Watts’ clutch play, bandaged hand and all, led Beloit them to their second straight title in a row winning 15-14. A local sportswriter witnessed the crowd’s thunderous approval of Watts’ extraordinary play and said, “no individual (had) ever received a greater ovation than did the crippled Watts.” In 1934, Beloit was favored to win a third straight state title, Johnny Watts’ and his team didn’t disappoint. Beloit dominated all their opponents, beating Wisconsin Rapids in the championship game 32-18, with Johnny scoring 14 of those points. Watts again received All-State honors, “Johnny was certainly the best basketball player I ever coached,” Jacobson said. A Capitol Times reporter wrote: “Watts is as fast as a streak, a great scorer and a superb defensive player. There remains but one possible thing that might keep him from greatness, but he has that –courage- and he has it plenty.” Dr. Walter Meanwell, the coach of the University of Wisconsin team said, “Watts is one of the greatest basketball players turned out by a Wisconsin high school.”Beloit’s Johnny Watts dominated Wisconsin’s state tournament as the only African American competing as a sophomore and junior. Jack Gilmore, another African American, joined Johnny during his senior year to assist in winning the 1934 state title.

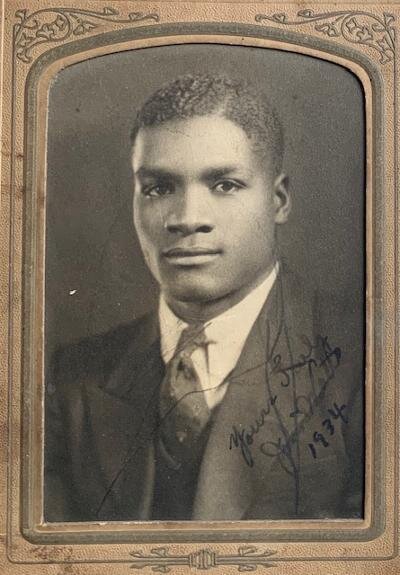

Johnny Watts, class of 1934 Beloit High School senior picture

Johnny Watts knew of the “unwritten gentleman’s agreement” about African Americans playing in the Big Ten or other colleges despite his stellar high school career. Watts decided to move to La Crosse, Wisconsin where his sister lived with her husband, to attend La Crosse State Teachers College. There Johnny continued his outstanding athletic career on the basketball court and football field for two years.

The following pictures are from the 1935 and 1936 La Crosse Teacher’s College Yearbook

Yearbook caption -Johnny Watts, graduate of Beloit High School, and former all-state high school forward, was one of the leading scorers of the team. His speed and shiftiness brought many a hand from the crowd.

Yearbook caption -Johnny Watts - Playing his first year for the Maroons he proved to be one of the best finds of years. Already he has gained the reputation of being one of the fastest and trickiest players in the conference. Passing, running and blocking seem to be a specialty for Johnny.

Unfortunately, circumstances led him to leave school, opening the door for Watts to barnstorm with the famous Harlem Globetrotters. “The Globetrotters were after me when I got out of high school,” Watts said. “After two years at La Crosse owner Abe Saperstein made me a good offer. Back then, if you made $30, that was good money.” He played for the Globetrotters for three before forming his own barnstorming team, the Negro Globe Trotters based out of Milwaukee. In 1950 Watts renamed the team the Harlem Aces and continued traveling across the country, taking on the duties of coach and manager.

By the mid 1950’s Johnny Watts moved to Milwaukee and began work at Harnischfaeger, a manufacturing company. He continued playing basketball in the industrial basketball leagues and softball leagues. Watts enjoyed helping the youth in the neighborhood develop their basketball skills and also shared his basketball knowledge with the Milwaukee North boys team.

John Wesley Watts died on January 25, 2001 in Milwaukee Wisconsin. He was inducted into the Wisconsin Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame posthumously in 2011, recognized as a player at Beloit High School.

There have been many African-American Beloit athletes that have taken the court with the same dream, determination and aspiration held by Johnny Watts more than 88 years ago - though they may not know that they are following a trail blazed by one great former Beloit standout.

![119 - Frank Clark[1] (1).JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e2f3e9e6f66be570cfe752a/1612367584347-NJTKQKNMEX9ELGAHHHK5/119+-+Frank+Clark%5B1%5D+%281%29.JPG)